Serbian wine history

Fossil remains of grapevine seeds and wine vessels at archaeological sites on the banks of the river Danube near Grocka, in Vinča and other places, indicate that the grapevine was present in now-day Serbia thousands of years ago. The first traces of viticulture and winemaking found on the territory of Serbia are vessels from the Bronze Age, around 2200 BC, and from the Iron Age, around 400 BC.

By the first century AD, viticulture had advanced so much that in 92 AD, the Dominican Emperor banned wine production in all Roman provinces outside the Apennine Peninsula, as the Roman Empire faced significant surpluses of wine on the market. The ban on growing vines lasted until the third century AD when it was abolished by Emperor Marcus Aurelius Probus (Marcus Aurelius Probus, 276-282). It is believed that the reconstruction began in Srem, in the vicinity of today’s Sremska Mitrovica (Sirmium), where Emperor Prob was born.

After arriving on the Balkan Peninsula, at the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century, the Slavs quickly got to know the vine, grapes and wine, accepting the cultural heritage of Byzantium, which has its origins in the ancient era.

During the Nemanjic dynasty, viticulture in Serbia experienced a great rise. In this period, it developed especially in the monastic estates – metos and estates of the Serbian nobility. The oldest known record of vineyards in medieval Serbia is in the Hilandar Charter of Stefan Nemanja, from 1198. It mentions Velika Hoča with two vineyards, which the king assigns to the Hilandar monastery. In the same, 12th century, Župa was mentioned for the first time, and Stefan Nemanja gave it to the Studenica monastery.

It is noted that during the reign of Emperor Dušan the Great (1331-1355) wine was transported by “wine pipeline” from the cellar in Velika Hoča (the village is preserved to this day) to the then capital Prizren, and Emperor Dušan legally regulated the obligation to cultivate vineyards, protect the quality of grapes and prohibition of mixing water and wine. It is also known that there was a person in the yard who took care of the cellar and served wine. The profession, known today as “sommelier”, was then the title “cup-bearer”, and it was carried by Pribac Hrebljanović, the father of prince Lazar Hrebljanović.

With the penetration of the Turks into this area, Serbian viticulture gradually declined. The population moved to the north, across the Sava and the Danube, bringing with them a vine. It is assumed that this is exactly how the Kadarka first reached Fruška gora, and then Hungary. Just like Furmint and Tamjanika (known in Tokaj as Sargamuskotaly).

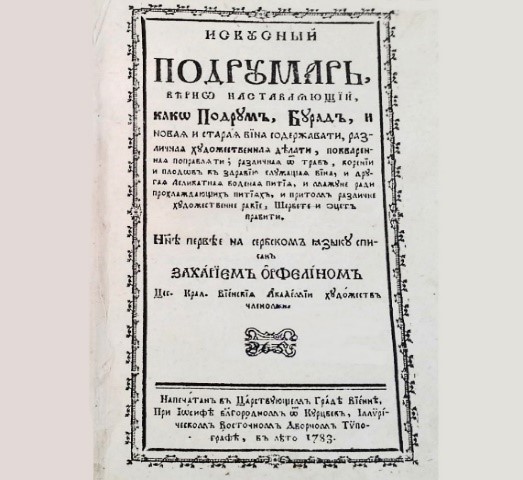

Zaharije Stefanović Orfelin was a prominent Serbian poet, historian, copper engraver, baroque educator, engraver, calligrapher and textbook writer. His book “Experienced Cellarman“ (Vienna, 1783) has several hundred recipes for making herbal wines, but it also gathered all the knowledge about making wines at Fruska Gora, but also French, Italian and German wines. Zaharije Orfelin also lists the recipe for making Bermet, which differed from house to house. This is the first book of its kind in the Serbian language.

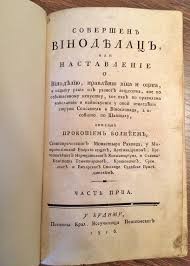

Prokopije Bolić, Archimandrite of the Rakovac Monastery, published in Buda (1816) the book “Perfect Winemaker”, in which he describes in detail 35 varieties of grapes, then grown on Fruška gora. For each variety, it explains its popular name and gives a botanical description and economic and technical characteristics.

After the renewal of the Serbian state and intensive development of viticulture, the golden age of this sector was interrupted in the second half of the 19th century by Phylloxera, which devastated a large number of vineyards. The renewal of the vineyards was fast and successful thanks to the establishment of vineyards. At the same time, wine-growing cooperatives are being established.

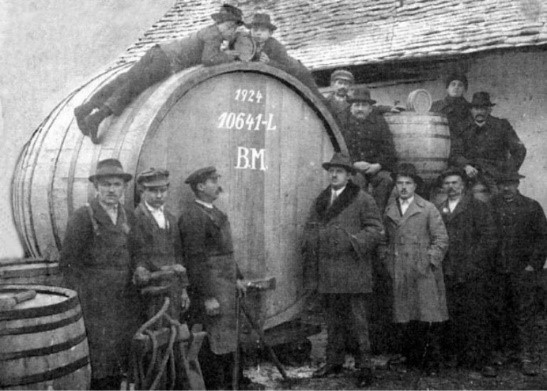

In 1848, in Zemun, the Moser family founded a winery and a wine wholesaler.

In the following decades, the Moser Winery successfully grew and resisted all adversities, and it also had the largest wooden wine vessel in the then Kingdom of Yugoslavia, of as much as 36,500 litres. Even during the Second World War, the winery did not stop working, and the owners left occupied Serbia in the middle of it.

After the war, as collaborators of the occupiers, the Mosers were deprived of all real estate. The new government renamed the winery the People’s Winery and Cellar – NAVIP, and very successfully continued to build the largest wine giant in the Balkans. In the period after the war, the production of wine continued, but also alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages. NAVIP owned 3,500 hectares of vineyards in Serbia and Vojvodina, and cellars in Zemun, Petrovaradin, Jagodina, Krnjevo, Vranje, Pirot and Leskovac. Basement capacities amount to 65 million litres, with the most modern devices for filling 52,000 bottles per hour. NAVIP was especially proud of the sparkling wine of the champagne type. The production process involved double natural fermentation. It remains for history that the capacity of the filling station in the “golden times of NAVIP” was not enough to meet the demand. We must not forget the plum brandy from the varieties Požegača and Crvena Ranka from the cellar of Crkvenac in Jagodina and Stari Vinjak according to the traditional cognac procedure.

“The first national public meeting of winemakers and winemakers in Serbia”, which was held in Nis on St. Trifun and Sretenje, on February 1st and 2nd, 1889 (at that time the old calendar was still used). The meeting discussed how to increase revenues from the sale of wine, the new vine grafted on an American basis, the export of wine to foreign markets, ways of associating winemakers and many other problems that plagued the then winegrowers and winemakers. On that occasion, the first evaluation of wine in Serbia was held, at which all participants of the choir who were engaged in grape processing brought their wines, and it was pointed out in the invitation to bring “one or two glasses (bottles) of their tasting wine “.

“Venčačka vinogradarska zadruga”, in 1903, 12 poorly educated peasants, except for the priest and maybe two other members, but good village hosts from the village of Banja near Arandjelovac, founded the first viticultural cooperative in Serbia, and they accepted their king Petar I Karađorđević. Later, his son, Aleksandar I Karadjordjevic, will become a member. This cooperative had one of the most modern cellars in Europe at that time. Our famous architect, Dimitrije Leko, designed a part of that edifice. The cooperative members had a modern production, and later they brought a German enologist. They produced sparkling wine by the traditional process, vermouth and cognac.

It was the production that raised the entire economy of this area. Over time, the cooperative grew into the titan of this part of Serbia and from 12 to 125 shareholders. In the next 30 years, the cooperative will have cellars at the level of the best European ones, they will export wines and sparkling wines. The basement reached a capacity of one million litres in 1929, and in 1938, at a time when there was barely any transportation between the towns, it received 10,000 tourists. Among the visitors was Eleanor Roosevelt, America’s first lady.

Between the two great wars, viticulture developed intensively again, but everything stopped at the beginning of the Second World War, and later continued with the development of large state estates and wineries to which everyone was obliged to sell grapes, which led to the cessation of personal production. The re-establishment of private wineries began in the early 1990s and their development is still ongoing.